Trying to fit History teaching pedagogy into small quotes is often problematic. I recently was confronted with this situation while reading a newspaper article. The piece, published in the Guardian Newspaper was written by British journalist Janet Street-Porter. For those not familiar with Ms. Porter, it would not be contentious to say that she often questions the norms of institutions, particularly the BBC. She is no stranger to ‘calling out’ what she sees as needing debate or reflection. I often find myself at odds with her, but I can say that over the years I am grateful for her contribution, because it makes me stop and think. On pausing, I can often see my own cultural bias obscuring an alternative viewpoint. The article goes on to talk about our approaches to educating about the past through television and drama productions. This poses the question; how do we tell about the past?

In many British Schools, the story of Guy Fawkes and the Catholic plotters who planned to blow up the Houses of Parliament in 1605 is still a popular theme during the Fall term. This is a key moment in British history and the subsequent capture and brutal public execution are ever popular thanks to ‘Firework night’ events around the United Kingdom. It has recently been turned into an opportune drama series by the BBC. The interpretation and dramatisation of this 1605 event still manages to stir contentions. Critics according to Porter, have complained that Gunpowder glamorises terrorists and sanitises religious bigotry, with some viewers finding the scenes of torture (a noblewoman stripped and crushed to death, for example) highly upsetting.

In Miss Porter’s opinion, the show is,

“the latest example of a fashionable dramatic genre; history-light – where colourful periods in the past are presented in a highly selective way, with glittering actors and expensive special effects and posh people sounding thoroughly modern.”

For those of us at all stages of education, the challenge is how you present the past in an age-appropriate way that does its best not to dilute what we really know and also accommodate new emerging revaluations based on new evidence. In an online article, Susan I. Kent presents just such a challenge.

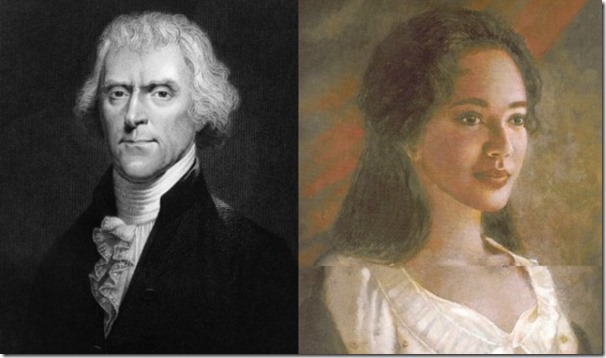

“Recently published test results indicating a DNA match between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings’ youngest son offers the most compelling evidence to date that Jefferson may indeed have fathered at least one child by this slave given to him by his wife’s father. It had been long established—but little publicised until now—that Sally Hemings, whose slave mother was owned by Jefferson’s father-in-law, was Martha Jefferson’s illegitimate half-sister. These findings expose today’s students to complex issues about human character and the nation’s past from which some might have preferred to protect them.

Sarah “Sally” Hemings was an enslaved woman of mixed race owned by President Thomas Jefferson. Most historians believe Jefferson was the father of her six children, born after the death of his wife

This sort of new conclusive information makes it even more challenging to present issues like the founding fathers’ of the United States ownership of slaves.

Hemmings rightly poses the question. Should this recent evidence be discussed, and, if so, how might teachers best present it? Not only are some issues difficult for young children to understand, many are inappropriate for classroom discussion, especially in the Primary phase.

While educators are presented with such evidence, we are asked to champion the values that make our nations great. In England, the Department of Education has been pushing British Values so that government can develop more community cohesion. However, it is very difficult to choose not to remember the injustices that the British Empire also exported in its wholesale distribution of British Values. Of course, I write these words in the time that I live. Many no longer regard the British Empire through the imperial spectacles of the past that frame it into the nations ‘glorious history’

So how do we reconcile the need for authenticity in our presentation of history at a time when a growing number of schools aim to instill in children moral values such as respect and honesty through a resurgence of character education programs using historical figures from the past?

An even greater challenge confronting teachers is how to help students analyse and evaluate the conflicting perspectives and values that have emerged as a result of this evidence. How can the great accomplishments of leaders like Jefferson be reconciled with the implied serious character flaws that now appear undeniable? How can moral issues, such as slavery and freedom, equality, sexual conduct, and the right to privacy be understood in the context of their times and be weighed to determine which are most essential to the survival of a democracy?

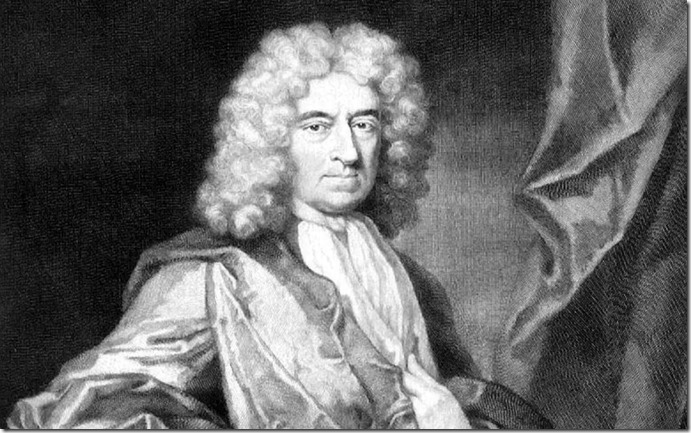

One such dilemma recently surfaced in the former Slave Trade importation port of Bristol England. Here a local school, Colston’s Girls’ School faced that issue. The school bore the name of a prominent Slave Trader and ‘philanthropist’. He was a deputy governor of the Royal African Company which between 1672 and 1698 who transported around 100,000 enslaved Africans to plantations in the West Indies and America. In 1710, Colston set up a school for “100 poor boys”, then handed over the management of the school and his endowment to the Society of Merchant Venturers of Bristol

Edward Colston Deputy Governor of the Royal African Company which between 1672 and 1698

I

The Headteacher Mr. Whitehead, in a letter to parents, said: “It has been suggested that Colston’s Girls’ School should change its name in order to remove the association with Edward Colston.

“We have considered this suggestion and we have listened carefully to views on both sides. After much discussion, it has been agreed that it would not be appropriate to rename the school.”

He went on to explain: “There is no doubt that Colston’s Girls’ School exists today as an outstanding school for girls, nationally known for its academic excellence and well respected for its inclusivity and diversity – because of the financial endowment was given by Edward Colston, but we see no benefit in denying the school’s financial origin and obscuring history itself.

“To the contrary, by enabling our students to engage thoughtfully with our past, we continue to encourage them to ask questions about present-day moral values and to stand up for what they believe is right.”

Are we in danger of ironing out all the complicated bits that don’t suit modern storytelling for a generation with a short attention span? Perhaps we need to work out how we can present the past without obscuring history itself even when we do not like our past.